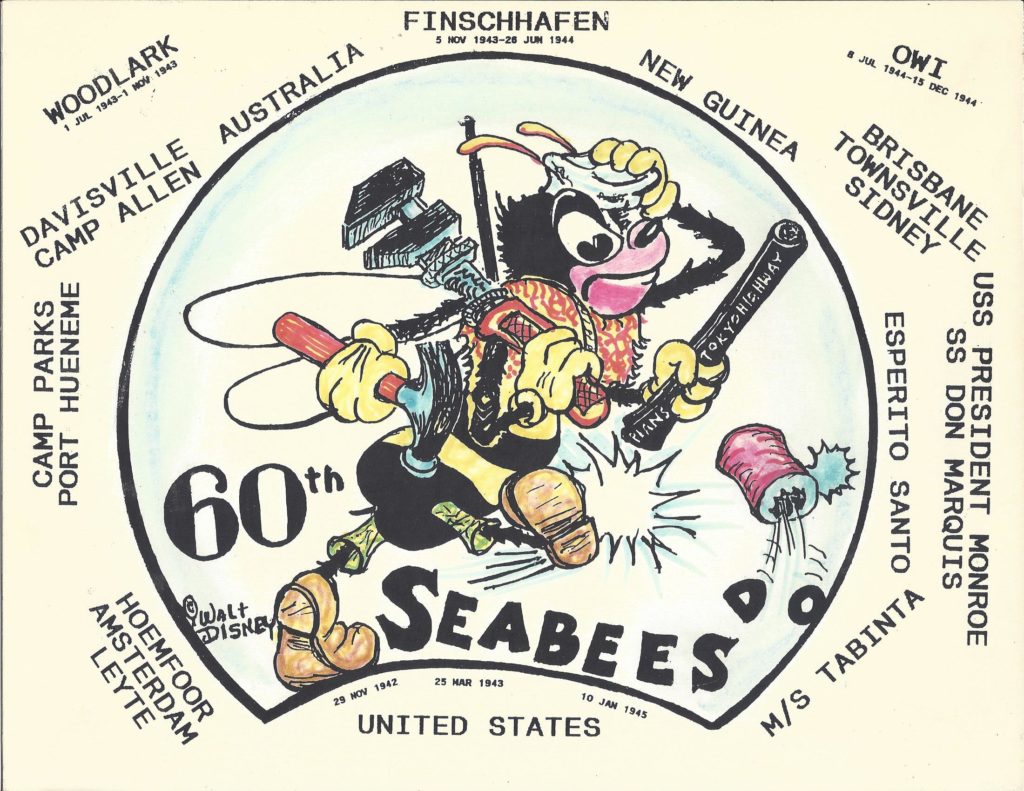

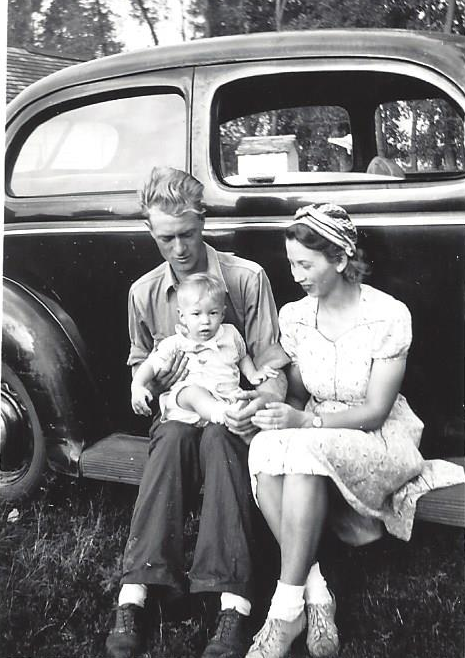

Wilfred Melvin Martfeld (Bill) registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, married Inez Merle Eyl on April 6, 1941, and saw the birth of his first child on November 9, 1941. Then a few weeks after the bombing of Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) Bill received his notice to report for active duty while working a construction site in Spaulding, Nebraska. He appealed to the draft board in O’Neill, Nebraska and received a six month delay in reporting in order to find a place for his new wife and son to live. Bill continued to work construction projects in Nebraska during the delay in reporting period. While working on an ammunition depot in Sidney, Nebraska a close friend suggested they go to the recruiting office and volunteer for the Naval Construction Battalions. The Navy Construction Battalion was organized specifically for WW II in December 1941 and adopted the pseudonym “SeaBees” as the phonetic pronunciation for “CB” (Construction Battalion).[2] Being skilled construction workers they were enlisted as Petty Officers 3rd class, a jump of three or four pay grades over normal recruits. Bill and his friend took their oath of enlistment in Denver, Colorado and were sent back home to await further orders due to a shortage of training accommodations. About the second week of November 1942 while working on an air base in Ainsworth, Nebraska, Bill received orders to report for training. He took his wife Merle and year old son to Rogers, Arkansas to stay with her parents during his tour of duty.[4]

Bill was transported by rail to Davisville, Rhode Island for basic training on about November 19, 1942. After four weeks of boot camp, he caught a very nasty bug (possibly catarrhal fever as identified by the Navy) and was hospitalized for a week which put him behind his original boot camp class. By Christmas, still weak with the infection, Bill also suffered a bout of homesickness which was likely shared by most of his boot camp shipmates. After basic training he completed six weeks of advanced weapons and warfare training then he and his fellow sailors commissioned the 60th Naval Construction Battalion and headed to California on February 11, 1943.[5]

The 60th arrived in Oakland, California on February 17, 1943 after six days aboard the train and were bused to Camp Parks near Livermore, California. Bill received five days leave with four days travel time so he was able to visit his wife and son before departing overseas. By March 9, 1943 with all stragglers back to Camp Parks from leave, the battalion was bused back to Oakland where they caught a train to Camp Rousseau, Port Hueneme, California and made preparations for deployment overseas. They boarded the SS President Monroe and headed for the South Pacific on March 25, crossing the equator on the 1st of April and participated in the crossing the line initiation where King Neptune converted Bill his shipmates from slimy polliwogs into trusty shellbacks. Continuing on through the New Hebrides Islands, they passed very close to the wreck of President Monroe’s sister ship, SS President Coolidge which hit a mine a few weeks earlier but suffered no casualties. They at arrived at Espiritu Santo Island (Vanuatu) on April 10 to offload some personnel, then continued on to Brisbane, Australia arriving on Easter Morning, 1943.[5], [6] The stay in Brisbane was much enjoyed by Bill and his shipmates as they experienced the luxuries of excellent food, drink and friendly people as expressed by Bill in his personal account: “A dinner with six eggs on a 16 oz. steak with thick slices of bread, milk to drink, vegetables and all the rest cost about 10 shillings“.

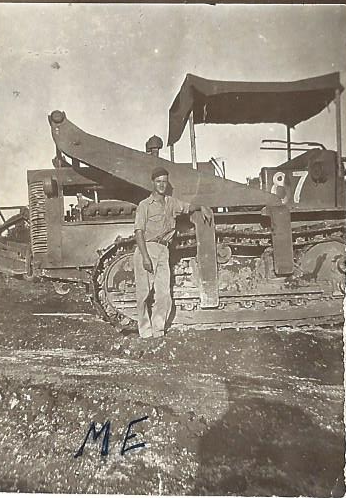

After about five weeks in Brisbane reorganizing, training and resting, the battalion deployed in several echelons for their advanced base and staging area near Townsville, Australia. Bill was in the second echelon, departing Brisbane on June 8, 1943 via a Landing Ship, Tank (LST). We sailed up between the coast of Australia and the great barrier reef. We were in sight of land at all times and it was very pretty. Here the battalion practiced and prepared for their first actual combat duty, Woodlark Island (Muyua Island). Bill arrived on Woodlark with the second echelon on 11 July, a little more that a week after the initial landing. After offloading the LSTs, the battalion immediately started building the runway. Woodlark was not occupied by the Japanese so rain, jungle and disease were the worst enemies. A day or two after landing a Japanese bomber paid them a visit. This was my first experience with someone trying to kill me. The air raid’s red alert was sounded and we took cover as best we could. Bombs falling down have an indescribable sound, a real death rattle that is not the least like the sound effects in the movies… This raid did very little damage as the bombs struck the earth and made a large crater, but most of the shrapnel and dirt was deflected upward. When bombs struck the tall trees and detonated before hitting the earth, they were deadly. In just thirteen days the battalion had finished enough runway to begin receiving aircraft; an Australian transport and a squadron of P-39 fighters landed. After three weeks on Woodlark, Bill once again got very sick and was hospitalized for another a week in the Army evacuation hospital to recover from jaundice. He fully recovered about the time work on Woodlark was completed and the battalion prepared for its next landing. In just three months the 60th Seabees had built a 6700 ft runway, six miles of taxiway, a control tower, a weather tower, a parachute building, a chapel, thirty-three miles of graded road, thirty-two aviation buildings, forty-nine miles of transmission line and 340 miles of telephone line then packed up three LSTs and headed for Finschhaven, New Guinea on November 2, 1943.

The plan was to land at Finschhaven after dark on November 5 and unload in order to have the LSTs back at sea by daylight. The landing site was only thirty minutes away from the Japanese base on Rabaul, New Britain Island. At about 11:00 PM the LSTs came ashore but could not run all the way up on the beach. Bulldozers were offloaded in about three feet of water and built dirt ramps up to the LSTs so all the other equipment could be unloaded. It was completely dark with heavy rain turning the ground to deep, sticky mud. Bill’s job, equipped with only a small flashlight, was to lead the equipment being unloaded from the LSTs and towed through the mud up to a parking area off the beach. At daylight the offloading was completed, the LSTs got underway and work began on the 60th’s second airstrip.

Only minutes from the Japanese air bases on Rabaul, Finschhaven was under constant air raid alerts. The armory department took the unused horns off of some GI trucks and put them up in the trees as air raid sirens. Once again Bill and his shipmates were ducking for foxholes and taking some casualties as Lieutenant Commander Davidson recalled: This place was hot stuff then, with Aussies arguing with the Japs within sight and sounds of us to the north, and with Tojo’s nightly visits [bombing raids]. On the night of December 4 the Japanese bombed Finschhaven killing two Seabees and severely wounding many others.[6] Dengue fever was the next jungle disease to battle and Bill caught it. While his case was more of a distraction than a serious health issue, some personnel did die from it. Finschhaven grew into a large base and major staging area for pacific operations where much better living conditions than those on Woodlark Island existed. Preparations were underway to retake the Philippines and some 300,000 military were staged at Finschhaven.

On May 13, 1944, after completing their assignments on Finschhaven, the 60th Seabees were granted R&R (rest and recuperation) in Brisbane. Bill went with a group to a seaside resort called “Sea Brae at Sandgate” where he enjoyed a private room with a real bed and mattress and excellent food. They loaded aboard the Liberty ship SS Don Marquis for the return trip to Finschhaven. The commissary department bought supplies including a lot of ice cream which the ship was not able to store so a weeks worth of ice cream had to be consumed at the pier undoubtedly making the 60th Seabees a very popular outfit with the dock hands. After some shaky seamanship (hitting a reef and loosing the main anchor) the ship arrived a Finschhaven and the battalion began their journey to the next island, Owi, arriving on 8 July 1944.

While a very small landmass (about one and a half miles long by two miles wide), Owi proved to be the perfect island for an airstrip; little mud and a lot of coral which was considered superior to concrete for building runways. As an added bonus, the supply chain by this time was finally catching up to demand resulting in better equipment, better food and refrigeration. Also a plus, the Japanese were loosing the air war at this point: I don’t recall ever being bombed on Owi Island. The air strip was used by B24 bombers and with a maximum range of about 3500 miles could reach all the way to the Philippines from Owi (about 1000 miles to Leyte Gulf). The 60th Seabees completed work on their 3rd and last air field and were ordered back to San Francisco, California. They departed aboard the SS Tabinta, a dutch transport, on December 18, 1944. Tabinta was turned over to the War Shipping Administration shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor and had participated in continuous operations in the South Pacific.[8] Boarding the old battle weary ship at Owi must have been pretty tricky: We had to board this ship while it continued to go in a circle, as it had not been back to its home port for six years and it couldn’t disconnect the engine from the screw… We boarded by climbing up cargo nets hanging over the side.

Tabinta arrived in San Francisco on January 10, 1945 and the 60th Seabees were bused back to Camp Parks. Two days after his arrival, Bill received his 30 day leave orders and left for Arkansas and home. Upon returning to Camp Parks, Bill learned the 60th would be decommissioned, which formally occurred on 30 March 1945. Bill was assigned menial tasks with the 136th battalion, a stevedore and transportation unit at Port Hueneme, until he was transferred to 19th Seabee Battalion. The 19th departed Port Hueneme on June 12, 1945 aboard USS Heywood (APA-6) arriving Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands on July 24 and set up camp at Chimu Wan (now U.S. Marine Corp base, Camp Hansen) where they, according to Bill, began building a huge supply depot to store everything in the world for the invasion of Japan.[9] After the U.S. Air Force dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (August 6 and 8, 1945), the Japanese announced their surrendered on August 15 and formally signed the instrument of surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. The Navy began discharging people according to their length of time in service. We volunteered in the Navy Reserve, and our enlistment was for the duration of the war so we were therefore sent back to the states to be discharged. Bill shipped back to San Diego aboard the USS Grimes (APA-172) and caught a train to the U.S. Naval Personnel Separation Center, Lambert Field, St. Louis, Missouri where he was honorably discharged on November 14, 1945. Bill joined his family in Avoca, Arkansas and remained in northwest Arkansas until his passing on 16 July 2001.

Between July 1, 1943 and December 18, 1944 the 60th Seabees performed three amphibious landings and constructed three air fields, the one on Woodlark Island was operational in just thirteen days, receiving may accolades for their tremendous accomplishments including one from General Douglas MacArthur: One of the air strips on islands near New Guinea [Woodlark], used in the smashing attack on Rabaul was conquered by the Seabees in 13 ½ days – a record for the Pacific.[2] The first American to die on Woodlark was John Robert Olm, S2c, killed in an accident. The 60th’s cruise book is dedicated to him and 12 other Seabees that died in southwest Pacific operations.

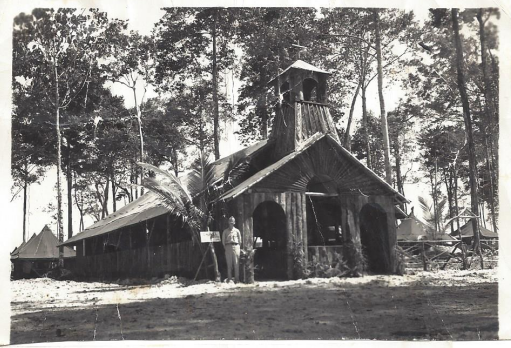

Bill told me about two memories of his service in the southwest Pacific. He was particularly proud of the chapel they build from coconut tree logs. A chapel was built on all three islands along with the airstrips and support structures. Bill was probably referring to the one on Finschhaven, Papua New Guinea as it received a lot of notoriety at the time. The battalion Chaplain, Watt Cooper, documents the chapels popularity with all the troops on the islands as Army, Navy, Marines and other commands in the area attended the services. The General Commission on Army and Navy Chaplains requested the Chaplain write an article on the chapel building program which appeared in the state-side newspapers.10 The Finschhaven chapel had a bell that was salvaged from an abandoned mission on the Island. I’m including a the first and last verses of a poem in Chaplain Cooper’s book about the chapel probably written by one of the battalion Seabees to demonstrate how important it was to the service members:

"A Chapel" by Marty OKeefe Deep in the jungle peals a chapel bell Calling men to forget their man-made hell, To come and worship a God Who's just, Who condones not man's petty lust For wealth or power or idolatry But gives all men the right to be free. And because they had this inalienable right These men went out to help end the fight. But in this chapel of their own Built with thoughts of God and home They find heart-ease and peace and rest, And find the strength to face the test Of longer days, weeks, months, yes, years, For God helps still their inward fears.

The other event was how he suffered a small injury to his ear when one of the trees they were trying to clear fell prematurely as a result of clearing the trees around it. Two of his shipmates were not so lucky and were killed as a result of falling trees. At the 60th Seabee reunion at Daytona Beach, Florida in September, 2000, I personally heard members talking about some of the Japanese air raids on the Woodlark, but I never heard Bill mention these. Fortunately, he documented them in his letter which I used extensively in this memorial to his World War II service. Bill and his wife Merle were members of “the greatest generation” and are both WW II heroes. While Bill was deployed, Merle moved to Avoca, Arkansas, went to work, bought the family house on 5 acres and continued raising a growing family as their first daughter was born in October 1945, just a month before Bill separated from Naval service.

Visit MM2 Wilfred Melvin Martfeld’s individual record.

Credits:

- Photo from Wilfred M. Martfeld WW II Photo Collection.

- Naval History and Heritage Command, “60 Naval Construction Battalion”, 60th SEABEES Cruise Book, 1945 accessed Jun 4, 2020.https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/museums/Seabee/Cruisebooks/wwiicruisebooks/ncb-cruisebooks/60%20NCB%2C%20WW%20II.pdf

- “Seabees in World War II,” Wikipedia, last modified June 4, 2020, accessed June 4, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seabees_in_World_War_II

- Martfeld, Wilfred Melvin, “My Experiences in the Navy Construction Battalions”, Letter dated December 7, 1985, https://family-roots.net/documents/My_Experiences_in_the_Navy_Construction_Battalions.pdf

- Naval History & Heritage Command, 60th Naval Construction Battalion Historical Information, accessed Jun 4, 2020. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/museums/Seabee/UnitListPages/NCB/060%20NCB.pdf

- LCDR Davidson Speech at 60th Seabees 1 year deployment Anniversary, March 25, 1944, https://family-roots.net/documents/60CB_LCDR_Davidson_Speech_25_Mar_1944_sm.pdf

- Map by Google Earth, annotations by Joe Martfeld.

- Roland W. Charles, Troopships of World War II, “TABINTA” (pg 304), (Washington D.C.: The Army Transportation Association, April 1947). Accessed Jun 4, 2020:https://history.army.mil/documents/WWII/wwii_Troopships.pdf

- Naval History & Heritage Command, 19th Naval Construction Battalion Historical Information, Accessed June 4, 2020, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/seabee/explore/seabee-unit-histories/ncb/19th-Naval-Construction-Battalion.html

- Watt M. Cooper, “With the Seabees in the South Pacific”, (Graham, North Carolina: Watt M Cooper, 1981).

Let us never forget.